Common Knowledge Sucks

Though lovable, humans fill themselves with old, often false, unshakeable beliefs.

I really like humans. They’re funny, tender, awkward, generous, ridiculous. They mean well more often than not. Which is exactly why you shouldn’t listen to most of what they say.

Most human speech isn’t perception — it’s inheritance. Beliefs absorbed early, repeated often, and defended long after they stop matching reality. That’s not a moral failure. It’s a structural one. Humans are shaped by stories before they have the chance to test them, and once a belief is anchored to identity, it becomes difficult to examine without feeling personally threatened.

This isn’t a condemnation. It’s an observation.

Humans talk constantly, but very little of that talk comes from direct contact with life. It comes from classrooms, screens, families, institutions, and social circles. From what was rewarded. From what kept them safe. From what helped them belong. Language becomes social glue long before it becomes a tool for seeing.

Listening carefully to what people say is often misleading. What matters more is where it’s coming from.

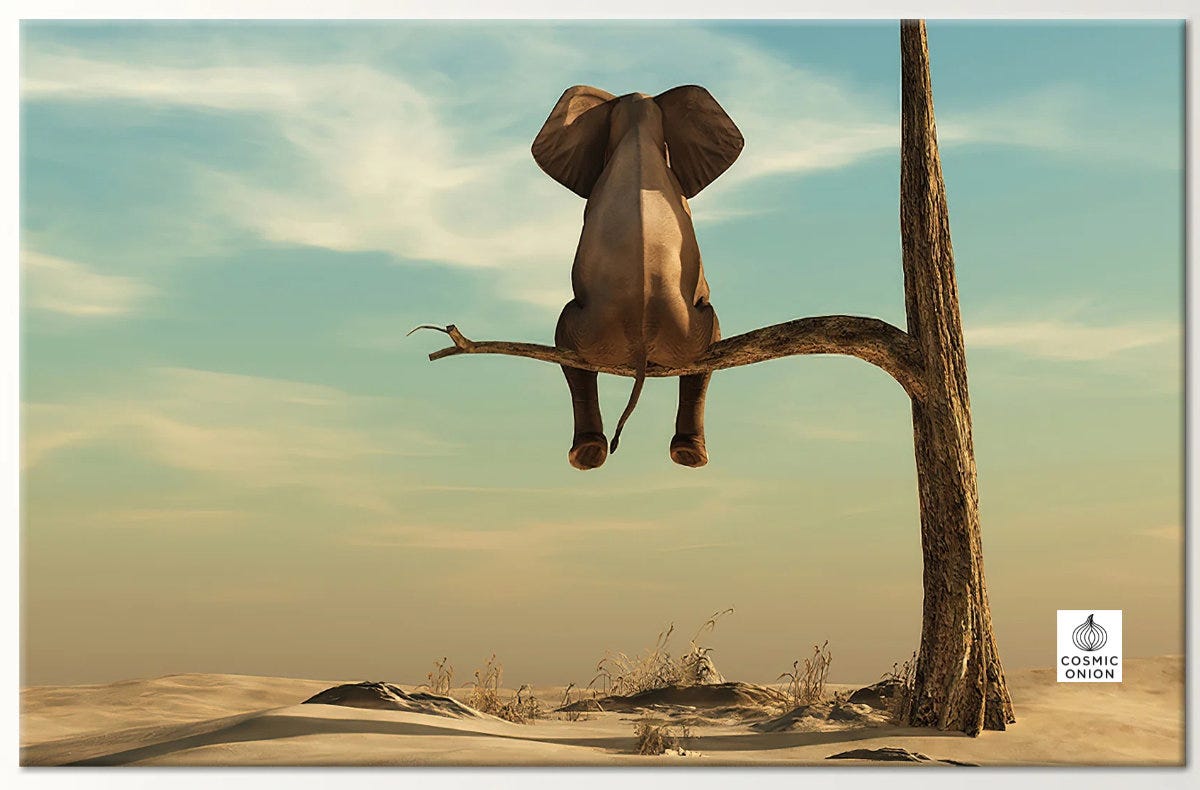

1. Common Knowledge, the Elephant in the Room

“Common knowledge” is the most powerful idea no one ever examines. It sits in the room, massive and unquestioned, while conversations politely orbit around it as if it were furniture instead of a living animal.

Common knowledge isn’t knowledge at all. It’s agreement.

It’s what everyone is assumed to know, which conveniently means no one feels responsible for verifying it. The moment something is labeled common, curiosity shuts down. Asking questions feels unnecessary, even improper. Doubt becomes a social violation rather than an intellectual act.

This is how beliefs become load‑bearing without ever being tested.

Take something simple and familiar: fluoride prevents cavities in children. Most people accept this instantly. It’s repeated by dentists, schools, public health posters, and well‑meaning parents. Ask how they know it, and the answer is rarely experiential. It’s just what you’re supposed to believe. Questioning it doesn’t invite discussion; it produces discomfort. Not because the idea has been personally examined, but because it has already been socially settled.

That’s how common knowledge works. It doesn’t argue its case. It skips the reasoning and arrives pre‑approved. Once an idea reaches that status, evidence becomes secondary to compliance, and doubt starts to feel like irresponsibility rather than inquiry.

Most people don’t believe things because they’ve tested them against reality. They believe them because everyone else already does. The belief arrives bundled with social safety. To question it risks friction. To accept it costs nothing. So it spreads.

Common knowledge thrives on repetition, not accuracy. It doesn’t need to be true — only familiar. Over time, repetition gives it weight. It begins to feel solid, inevitable, even natural. People orient around it without noticing they’re doing so.

This is why intelligent, kind, well‑meaning humans can defend ideas that quietly fail them. The belief isn’t held consciously. It’s ambient. It’s in the air. It’s simply how things are.

And because common knowledge presents itself as neutral background, it escapes scrutiny. It doesn’t announce itself as ideology. It feels like reality itself. Questioning it can sound strange or extreme, not because the question is unreasonable, but because the belief has been insulated from inspection.

History is full of once‑unquestionable truths that collapsed — not under debate, but under contact with reality. They didn’t fall because someone argued better. They fell because the world stopped cooperating.

The elephant in the room isn’t that people believe false things.

It’s that everyone assumes someone else has already checked.

2. Speech Is Not Seeing

Humans confuse fluency with understanding. If someone can speak smoothly, confidently, and at length, we assume they know what they’re talking about. But speech is cheap. Seeing is not.

Seeing requires contact. Consequence. Time.

Most speech is recycled. It’s language passing through a human body without ever touching the ground. The speaker feels sincere because the belief feels familiar. Familiarity is mistaken for truth.

That’s why advice so often fails. Most advice isn’t insight — it’s reassurance. It reassures the speaker that the world still works the way they were taught it does. Accepting it pulls you back into old maps long after the terrain has changed.

Listening to people who haven’t paid the cost of their beliefs is like taking directions from someone who’s never been there.

3. Why Empires Prefer Belief to Force

Empires don’t rely on violence alone. They rely on normal.

Managing belief is easier than managing bodies. Once an idea is installed deeply enough, people will defend it on the system’s behalf, convinced they’re protecting something personal. Power becomes invisible when it feels inevitable.

This isn’t because humans are weak. It’s because they are social.

Belonging is a powerful incentive. Humans will protect the stories that keep them included, even when those stories quietly harm them. Not out of malice. Out of fear of exile.

When belief becomes infrastructure, questioning it feels like sabotage. Compliance feels like responsibility.

That’s how systems persist long after they stop serving life.

4. Midnight and the Thinning of the Noise

Clarity often arrives late at night. Not because something mystical descends, but because the noise recedes.

The phones go quiet. The borrowed urgency fades. The inner hall monitor relaxes. What remains isn’t dramatic — it’s unmasked.

This is when writing becomes easy. Fingers move without forcing. Sentences form without posturing. You stop trying to sound right and start naming what you’ve seen.

People who read words written from this place don’t feel persuaded. They feel recognized. Not because they learned something new, but because something familiar was finally said plainly.

That isn’t influence.

That’s remembering — re-membering.

5. Listening Differently

To not listen blindly is not to reject people. It’s to refuse to outsource perception.

I don’t listen to most humans because I care about what’s real. I listen to patterns. To consequences. To what repeats across cultures without being taught. To what costs something to say and offers no easy belonging in return.

Humans are lovable. They are not reliable narrators of reality — and they don’t need to be.

Their value isn’t in their certainty.

It’s in their capacity to notice, to feel, to hesitate, to change.

Listening differently isn’t an act of superiority.

It’s an act of respect — for them, and for yourself.

Because beneath all the borrowed beliefs, something else is already present.

Knowing is a different animal.

It isn’t learned. It isn’t granted by authority. It doesn’t arrive through consensus. It’s innate — a quiet, built‑in compass every human carries. The old image of an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other was never theology. It was shorthand for something simpler: an internal sense of rightness, a felt recognition that precedes explanation.

That’s consciousness itself.

Not as an abstraction, but as the background condition of being alive. The thing that notices before it names. The thing that feels before it reasons. It doesn’t come from matter — it arrives with it, moves through it, and outlasts whatever stories get told about it.

And that’s why the mind parasites work so hard to convince you it isn’t there.

If you can be convinced that knowing is external — owned by experts, “authorities,” institutions, or systems — you’ll keep listening outward instead of inward. You’ll trade recognition for permission.

Listening differently means remembering you were never meant to live that way.

You don’t need permission to know.

You need the courage to stop asking.

References

Clif High — Substack Essays & Videos

(Event stream, perception vs belief, narrative collapse, recognition over persuasion)Walter Russell — The Nature of Reality

(Knowing precedes learning; consciousness as primary; seeing vs repeating)Richard Berry — Supreme Consciousness Is Primary

(Direct knowing, pattern recognition, refusal of outsourced perception)Thomas Kuhn — The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

(Paradigms persist through consensus until reality no longer cooperates)Ivan Illich — Deschooling Society

(Institutionalized belief, credentialed knowing, loss of direct experience)George Orwell — Essays on language and power

(Normalization, consensus reality, belief as control infrastructure)

I like people with street smarts compared to book smarts, it's a more authentic conversation that I really learn from.

The life we live is the content we create, it's important and it matters.

For example some of my content involves sailing around the world on oil tankers, LNG ships etc.

Cleaning up hazardous waste sites as a heavy equipment operator, working in a scrap metal yard and even burying bodies at a cemetery.

It also involves things like walking on hot coals, the arrow break, walking on broken glass and throw in a couple of 40 day water fasts that I've done.

This is the content I've lived that has meaning and purpose, although so misunderstood as you wrote with talking points following a preselected indoctrinated answer from people that are emotionally not ready to handle a different way of understanding.

Thanks for listening.

Thanks for sharing.

I was just telling my grown son about how words are spells.

How people fashion their words to be purposely vague, and yet imply something that they have not actually said.

They entice you to assume their meaning without saying it implicitly.

I have had to learn to never assume or project meaning from someone's words.

If they are non-specific, confusing or vague, I will tell them I don't understand and to clarify what exactly they are saying.

Some people do it accidentally, but some people use it as a "charm" to imply something they have not stated specifically.

You can always tell the latter because they will become irritated or triggered when you request clarification. It exposes their game.

I know you're talking here about unexamined beliefs, but it kind of goes along with this discussion.

The "common knowledge" argument can be used in the same fashion.